There are a lot of things I feel like saying, but I won’t because my dad would have not wanted it… he hated any type of conflict and always preferred people to be kind toward each other regardless of the circumstances.

Unfortunately this was not how he was raised, Granddaddy Ted was a notorious authoritarian, he was extremely strict with my Dad and his twin brother Harold when they were growing up. My father would often tell me what seemed like horror stories about the alcohol fueled beatings they would receive as children. And how if they didn’t get good grades, work hard at the shop everyday after school and didn’t do every single little thing right… he feared his life would be destroyed. So they ALWAYS did EVERYTHING right because they really had no other choice.

In part these stories were to illustrate how lucky he felt I had it, but they were also HIS promise that he would do his damnedest to break this cycle. And that is exactly what he did.

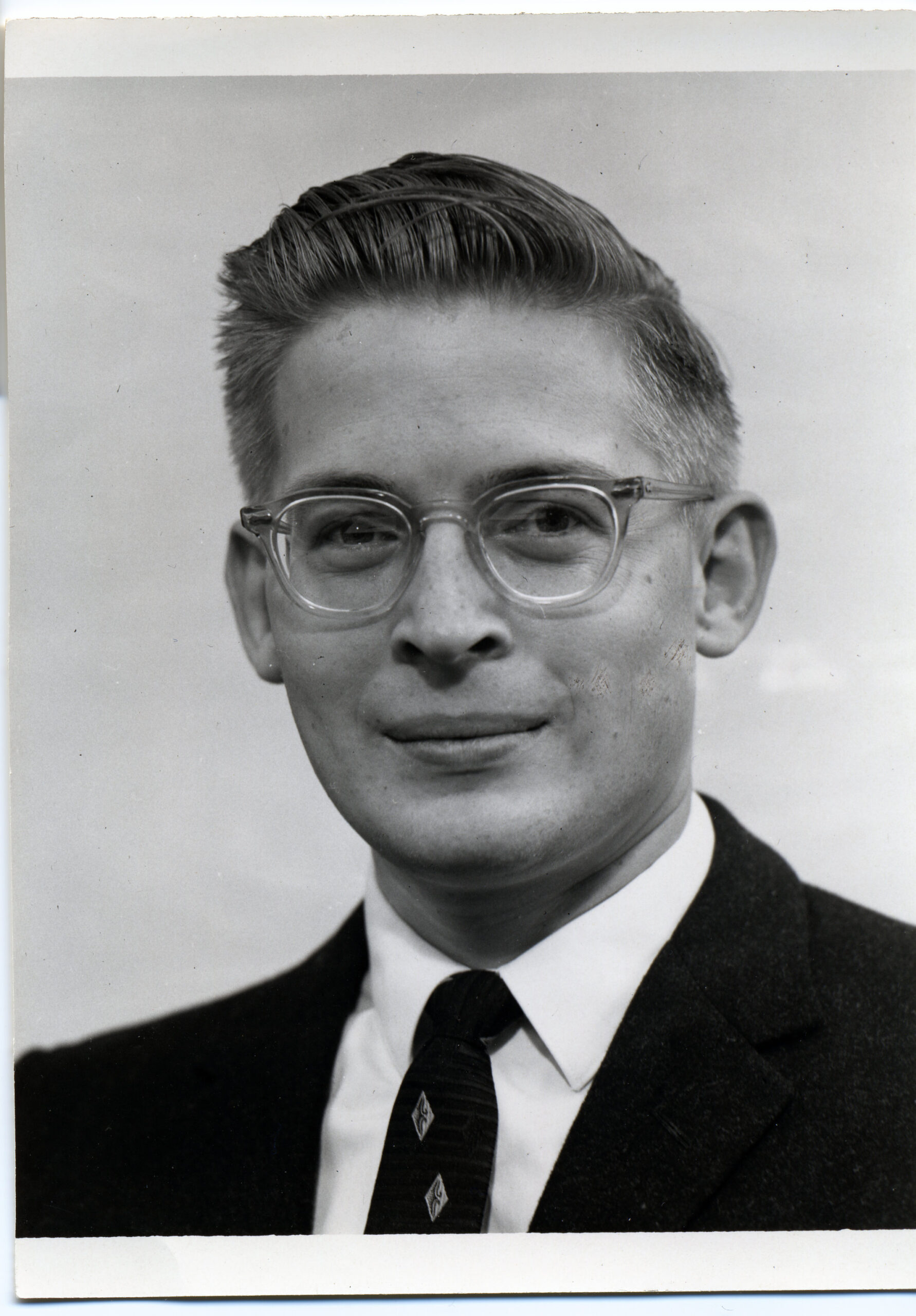

He was not just a loving, kind and patient father, he was literally my privilege in life. Everything that I am, my integrity, my drive, my intelligence, my love for science and storytelling, the very way I think, was all modeled after him.

He had an almost religious veneration for the sciences, particularly in physics and cosmology. One of his favorite things in this world was to read about new discoveries in Scientific American magazine. And when I was old enough to begin to understand some of its content, he would delight in reading me article after article, trying his best to translate concepts in quantum physics into a 3rd grader’s aptitude.

I’m sure a lot of people saw my dad as a very introverted, soft-spoken, engineer-type but in the right environment he was just as talkative as anyone else. I feel he understood that most people just didn’t care about the things that he found most fascinating, he didn’t want to bore everyone with the details. Growing up having a twin who shared his passions meant that they didn’t need other people, they could forge into the unknown together, both in science and literally because they grew up to be avid outdoorsmen.

They were always pushing each-other to be better. Better at chess, harder working, more efficient, more knowledgeable… by the time they reached adulthood, they had already left this planet. Like proper engineers they had over-optimized their brains to work in a very specific way, forever cursing their ability to make small-talk at parties.

My dad didn’t think of himself as an artist but he was one of the most creative people I have ever known.

This perception was due in part to a drawing assignment that he was given in grade school, when he showed his work to his teacher he was unfortunately told that he should probably never draw anything ever again… so he didn’t, but even at that young age he knew that his strengths lay in working with technology. Granddaddy Ted was one of the best automotive engineers in the country, which was one of the higher-tech jobs you could have at the time, but my father and his twin were determined to master the then emerging science of electrical engineering.

They were obsessed with space and science, they took a lot of pride in figuring out the way things worked. As teenagers, they did things like building their own Tesla coil, constructed radios from Heathkits, went on many backpacking adventures into the wilderness where they learned survival skills, and further honed their technical abilities. They got into reading sci-fi which even further stretched their imaginations of what was possible. They bore witness to America’s space program in its golden age, glued to the newly invented television sets as the first humans walked on the moon… they were hooked.

As an adult, my dad continued to have an obsessive drive, he never really was not thinking about engineering. He would get off his job and still be working in his head, scribbling diagrams on napkins at restaurants trying to get the idea out as fast as possible, because he was actually doing physics in his head without the aid of a computer, which in itself is a dying art form.

He tried to teach me the high level stuff right out of the gate because he believed that intelligence could be cultivated. He made sure I had a framework for understanding the world around me, he taught me how to look for patterns because they repeat, sometimes in entirely different contexts. He taught me to tinker, to learn for myself through experimenting, a skill that I have made a living off of to this day, and is at the very core of my artistic practice. He taught me that all things creative or technical can be seen as problems to be solved. And that any success was usually preceded by a series of failures. He taught me to trust my intuition because he understood that our brains are sometimes bigger than just the conscious parts.

He taught me that there was a shape to the world, a weight to it, a way in which it moves that is vital to all artistic or technical endeavors. Concepts like balance, order of operations, contrast, and flow. He had great knowledge of materials, the tactile feedback of using tools, how to build something strong and make it look nice. And most importantly he taught me about the humility and perseverance needed to keep trying, to keep pushing out on the unknown, because that is what goes into “good engineering”, his highest aspiration.

He was my greatest teacher, he was my Warhol, my Einstein.

My father was a very kind, patient, and moral man, but he was by no means perfect. There were many things he did and choices that he made over his lifetime that he lived to regret. He would tell me about these regrets throughout my childhood because he wanted me to understand that he was not without flaws, but he also hoped I would not make the same mistakes in my own life.

His father ran a pretty “tight ship” when he was growing up, especially for the boys. It was the late 40s / early 50s and things were admittedly much different back then, men were taught to be strong and stoic. Granddaddy Ted didn’t want the twins ending up like those degenerate American kids. He would raise them with a proper Danish work ethic. A man’s place was to be the provider, to work hard and be dedicated to his craft. You have to be tough out there and you can’t be a big cry baby! And furthermore, kids are just pieces of shit anyway and generally have nothing good to say, and shouldn’t speak unless they are spoken to… at least that was what HIS father used to say.

In the home, at school, and working in my Grandaddy’s shop he was given a very short leash. He learned how to “be” in that environment, pushed himself to be the smartest, the most talented, the most hard working. And when my dad and his twin matured they continued to push each other in this way. They became experts in their field, they got their degrees in electrical engineering, and it was time for them to go out on their own and master adulthood.

Then something went very wrong, Harold fell in love and decided to move away with his new wife Karen to start a family, and my father was left alone for the first time in his life. His relationship with Harold was the most significant bond that he would ever have with another human being, and the loss of their life together left him extremely depressed, but men didn’t have emotions in those days so he threw himself into work and a relationship with Helen whom he barely knew at the time, they were soon married and having children of their own, they had 3 baby girls over the next 6 years. Karen (named after his brother’s wife who gave birth to his nephew Arnold, who was named after him), and then Christina, and finally Lois.

Money was tight at the time, but he had a family to provide for. He chose his career over his new family and would work 70-80 hour weeks and sometimes only came home on the weekends, and sometimes not even then. This was one of his greatest regrets in life. At that time, he felt that he had no other choice, although I think he later came to understand that he could have done better and he did try to do better with me. We spent a lot of time building things together, going on hikes, doing science projects and reading sci-fi for hours on end. In a way, I was ‘spoiled with attention’, his guilt resulted in my privilege. And although he tried to be a better father to the girls when they became adults, the damage was already done and I believe he came to accept this as well.

He was a bit of a work-oholic, when he was deep into a project he would do little else with his time. He would work 12 hour days, come home and then work late into the night. Speaking from my own experience, there is a level of engagement where one’s brain is almost singularly focused, where obsession can be a positive. It is a powerful feeling, not unlike a drug in both the way it stimulates the brain and the way you feel when you have to come back to earth.

And although I am forever thankful that he taught me how to go on my own “voyages”, I also know how all-consuming it can be and how easy it is to ignore my own needs, not to mention the needs of the people around me. I suppose if you find a way to make it through this world and make enough money with your obsession, and you can still put in the time to maintain your relationships, then you end up with a life well lived. Although I feel this is a tricky balance, and I expect that most people with this sort of chemistry are probably making compromises somewhere, hopefully it is worth it.

I do think despite his mistakes he felt like his contributions to aerospace HAD been worth it. When he was the age I am now, he was in the mission control room at NASA watching the Mariner satellite do a flyby of Mars. He had a major part in the design of the communications array and its camera system. He once told me that the suspense and excitement that he felt in that room was the pinnacle of his career and one of the most exciting moments of his life. The countless hours he had put into it, the innovations that it had taken were pushing against our understanding of physics, pushing out into the unknown to expand our understanding of the universe. This was at the heart of his passion and what he basically dedicated his entire life to.

My father was a boy-scout, he taught me to do good deeds and serve the community. To the world he was a very soft-spoken, rule-following conformist, but he also had a surprisingly rebellious nature that I think only a few people understood.

Under the surface was always this sort of unease, I suspect it was his “strict upbringing” that had left him sort of broken. He pretty much neurotically worried about everything all the time, he had trouble relaxing. He felt most comfortable in service, not in deciding things but in implementing them. He almost needed someone to tell him what to do at all times. You could see this in his career and in the partners he chose. In a way he just liked having a leash. It made him feel secure, like he had a place and purpose.

I believe he felt that in a way he had been psychologically compromised, his first authority figure had maybe pushed too far, and he would forever both crave and distrust the leash. And I suppose we all bond our lives with something on some level, but again he wanted more for me. He refused to clip my wings, he taught me to question authority. He taught me that no man was above physics, that no institution was without flaw, that all assumptions should be questioned and reexamined. He taught me to behave by a moral code that was not imposed, or borrowed from some book, but to make up my own mind, to explore and test my own understanding of the world around me, and make my own decisions… like a proper scientist. He wanted me to be independent, to make my own way.

He taught me that there is a physics in psychology, a science to human behavior. Those who didn’t see him as a “people person” didn’t understand who he actually was. He studied people as deeply as he did the cosmos, and I would argue that in both domains, he understood a little too much. This tends to humble a person, they remain silent when others speak on things they don’t even know. He might have been soft spoken, but the words he did say often spoke volumes.

In my young adulthood, I remember having this feeling that there were so few people I really looked up to, and only now in his absence do I finally understand why. I already had the privilege of having the best damn role model I could ever hope for, my own father.